Machiavellian: A Word with a Knife Hidden Behind Its Smile

Some words arrive politely. Machiavellian is not one of them. It slips into the language like a strategist walking into a crowded room, already calculating every exit and every advantage.

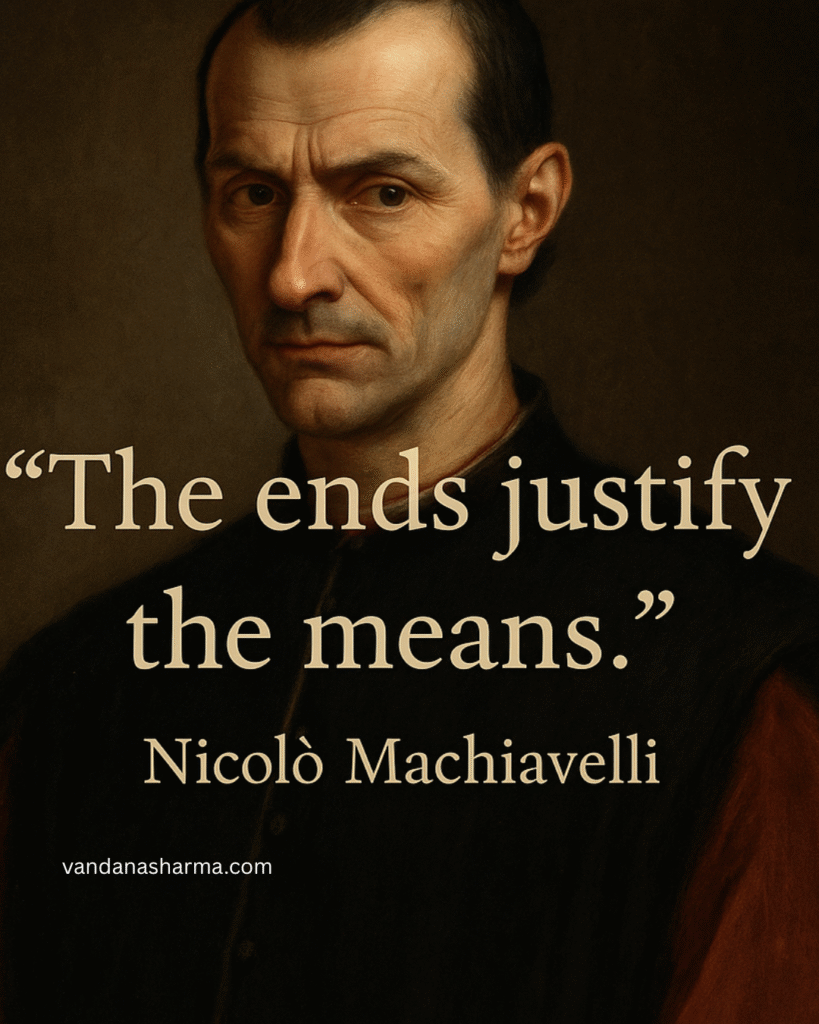

To understand the word, you need the man behind it, Niccolò Machiavelli, who never pretended to be a saint, and the world never mistook him for one. Portraits show him with thin lips, an aquiline nose, and eyes that look as though they’re dissecting you purely out of habit. He wasn’t diplomatic, but his mind was razor sharp and deeply analytical.

For years, he served the Florentine Republic as a diplomat and civil servant, navigating a political landscape where alliances shifted as fast as the weather. Then the Medici returned to power in 1512. Machiavelli had worked for the opposing side, which was all the reason they needed to dismiss him, interrogate him, and shove him out of the political sphere entirely. The exile wasn’t personal; it was simply how Renaissance politics handled inconvenient loyalties.

Cut off from the work that defined him, he turned to writing. If he couldn’t practice politics, he would study it. If he couldn’t serve the state, he would peel apart the machinery of power and show the world how it actually worked.

This is how Il Principe was born, from frustration, clarity, and brutal honesty. Machiavelli portrayed rulers realistically, with their ambitions and struggles, not as perfect moral figures. He described power the way a surgeon describes anatomy, clean and unflinching. That clarity earned him the reputation of being cynical and wicked.

Because of this work, he is often called the father of political science, not for inventing politics, but for studying it with the cool eyes of someone who refused to look away from human nature, even when it wasn’t flattering.

And from him came the modern meaning of Machiavellian, someone shrewd, calculating, and willing to manipulate when it suits their purpose. Someone who plays the long game. Someone who understands people well enough to use their weaknesses, fears, or desires like tools.

Most of us encounter a Machiavellian personality sooner or later. The charming colleague with an agenda. The leader who speaks sweetly and acts ruthlessly. The friend who pulls invisible strings while calling it “help”. They rarely raise their voice. They simply manoeuvre until the board tilts in their favour.

Still, the word isn’t pure poison. At its best, it describes foresight, strategic thinking, and the ability to stay calm when everyone else is ruled by emotion. In a complicated world, those traits can be useful, even admirable, when paired with a conscience.

But let’s be real. When someone calls you Machiavellian, they’re not complimenting your planning skills. They’re warning you that your moral compass seems suspiciously optional.

Machiavelli didn’t set out to create a villainous legacy. He set out to understand power. His ideas made people uncomfortable, yet they kept reading, because deep down, they know he wasn’t wrong.